All of Us Strangers, longing and Australian chardonnay

- Anna Jane Begley

- Feb 28, 2024

- 3 min read

Updated: Apr 1, 2024

“The past is to be lived with and not in.” That’s not a quote from All of Us Strangers, but from film critic Mark Kermode’s review and neatly forms the crux of Andrew Haigh’s tale of grief and desire – that tension between wanting to move on from tragedy, but to also wish the past back into existence.

The story – based on the 1987 novel by Yamada Taichi – centres on Adam (played by the ever marvellous Andrew Scott), a screenwriter attempting to write about his parents’ death that occurred when he was child. He seems detached from the world, immersing himself in Eighties songs from Pet Shop Boys and Frankie Goes to Hollywood in his high-rise flat in London. Even that seems disconnected, towering above the noisy streets below, looking out into the dark calm skies that encompass it.

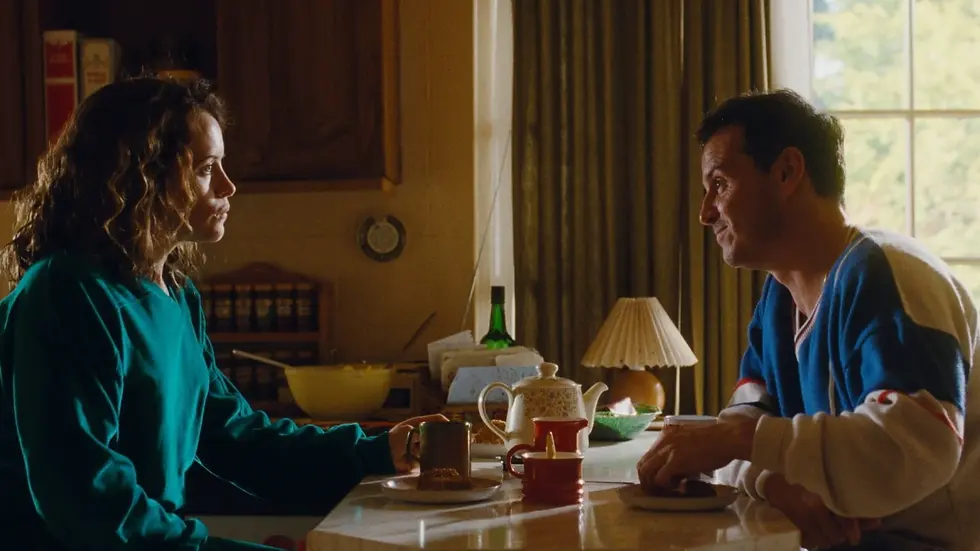

Just as a spark begins to blossom with his young neighbour Harry (Paul Mescal who still looks beautiful regardless of the creepy moustache – a homage to Adam’s dad in a disturbing male Oedipal way), Adam can suddenly see and converse with his parents’ ghosts who are residing in his old family home.

No longer a shy, bullied child, Adam is a middle-aged gay man who uses this phantasmal opportunity to “come out” to his parents, but to see it as simply a LGBTQ+ film misses the point here. It’s about longing and the way it can both comfort and hinder us. When Claire Foy, who plays Adam’s mum, looks at her child’s grown, muscular body she remarks: “But you were just a boy”. It’s one of many tender moments and encapsulates this conflict between wanting to hold onto the past as it brings comfort and love, but also the realisation that, if time must move forward, then so must we, no matter how hard we try to push against it.

Adam’s sexuality is one, but not the only, example of this: despite his desire to live in the past, many aspects of him as a person have moved on from his childhood, he has grown into a relatively confident man, comfortable in his sexuality and with a successful career. He tries to persuade his mum to move with the times, talking to her about modern perceptions on LGBTQ+ couples and – to her surprise – families, but she remains firmly in the Eighties with fears of prejudice and loneliness for her son.

Conversely, Adam finds his own views challenged by the much younger Harry (the age gap made explicit when debating the use of the terms “gay” and “queer”) who tries to prise Adam out from his shell, taking him to a nightclub where Harry too remains rather rooted in his upbringing, ordering a pint rather than the shots the crowd around him are downing. Again here, Adam can’t quite give in to the present, the red and blue strobe lighting morphing into the lights of the police car that arrived the evening his parents died.

It’s this tug-of-war between the past and present that has inspired this wine pairing, and I will take a moment to credit my good friend Charlie for the idea. Charlie, who is also an environmental lawyer and activist, is moving to Australia this week and so this pairing is dedicated to him.

Australian chardonnay has also shed itself of its buttercup-coloured ghosts of the Eighties, albeit these apparitions take a much lighter tone than those in the film. The oenologcial ghosts of the past were over-oaked and mass-produced, using inferior oak chips (rather than barrels) to give their wines a woody, overly-vanilla taste. It was so naff it essentially became a caricature of itself.

Nowadays, Australian chardonnay is crisp and balanced with ramped-up acidity and toned-down butteriness. A great example is Mulline Vintners’ Portarlington Chardonnay. It uses 20% new French oak to give it a slight toastiness, alongside flavours of lemon peel, sea salt and green olives.

The winery itself is run by Ben Mullen and his partner Ben Hine who employ extensive sustainability practices, such as using locally-produced lightweight bottles and minimising the use of non-organic materials (quite a feat for an Australian vineyard). Their winery revisits classic grapes of the past, but brings in modern practices to try and change the perception of Australian chardonnay, as well as other varieties such as syrah and pinot noir.

Haigh’s emotive portrait dishes out both hope and despair in equal measure, and lingers in the heart far longer than you really want it too; itself a conflicted ghost. I can only hope this chardonnay provides some solace as you cry into the popcorn.

All of Us Strangers is in cinemas now; Portarlington Chardonnay (AU$60) is available directly from Mulline Vintners for delivery in Australia (you're welcome, Charlie).

Comments